For our second post in our Deep Dive series, director Seth Eisen and I (Jax Blaska, research & production assistant) sat down to talk about the rise of gay bar culture in the early 1960s and how that contributed to the burgeoning gay liberation movement. The transcript of our conversation is below, along with links for further reading and historical context for certain happenings. Italicized segments below are pop-out context/deeper info on the topics we touched on. Enjoy!

Jax Blaska: What feels most important to you, when we think about (gay) bar culture in this time? How was this a shift from what came before?

Seth Eisen: The first thing that comes to my mind is the words: Safe space. And the other thing that comes to my mind is Romeo’s Pizzeria.

Image courtesy of https://www.foundsf.org/index.php?title=The_Black_Cat_Cafe

Romeo’s Pizzeria stood at 1605 Haight St., where Relic Vintage now lives. From 1964-1965, Romeo’s was the location of drag performer, activist, and eventual candidate for SF supervisor Jose Sarría’s operas. His performances’ typical location, the Black Cat Cafe on Montgomery St. in North Beach, closed that year after its owner had fought long and relentless legal battles in court for over 15 years.

I think it’s really interesting that that marked the transition in a way, because that year was really significant, in that the Black Cat closed after their long legal battle. Sol Stoumen, the proprietor, was a kind of incredible guy, I’m really fascinated by him. He was a Holocaust survivor, and a straight man, but his bar catered to all types of people — the Beats gathered there, older locals from the neighborhood, and of course, the gay crowd. There was so much police harassment going on, all about serving gay people. First of all, you could not be an out gay person as an owner of the bar, because if you’d ever been convicted of a crime against morality — which many people were, for soliciting or performing a lewd (homosexual) act — you were prohibited from running a bar. Women could not serve alcohol, (or even, in some places, legally enter a bar) so there was always a man working the bar. Even at Maud’s, the longest running lesbian bar up in Cole Valley, they had male bartenders, because that was the law. The ABC -- Alcohol Beverage Control board — had lots of control over how all these laws went, and then they were all tied together with Catholic, or Christian, politics and morality of the era, moving from the early 20th century into the mid 20th century. Mr. Stoumen took them to court a number of times, to the California Supreme Court, and he actually eventually won.

Landa Lakes performing as José Sarria outside Black Cat.OUT of Site.NorthBeach. Images courtesy of Chani Bockwinkle

But anyway, this is just to say, it’s an interesting thing that José’s stint at Romeo’s Pizzeria coincides with the closing of [the Black Cat]. Stoumen is such an important person, I think, in the fight for being able to serve queer people, and for queer people to be able to gather legally in a bar, because that was our safe space. And then there was this whole ring of police harassment and bribery — bribing the cops. So, regularly, a cop would come in, he’d give him the hundred bucks, or whatever it was, for that day, and then they would not bug them. And if not, there’s a whole bunch of arrests, and all that shit. This also brings in the beginnings of SIR, the Society for Individual Rights, and then also the Tavern Guild. They were one of the first gay activist organizations to gather power and the rights of queer bar owners and business managers to not be bugged.

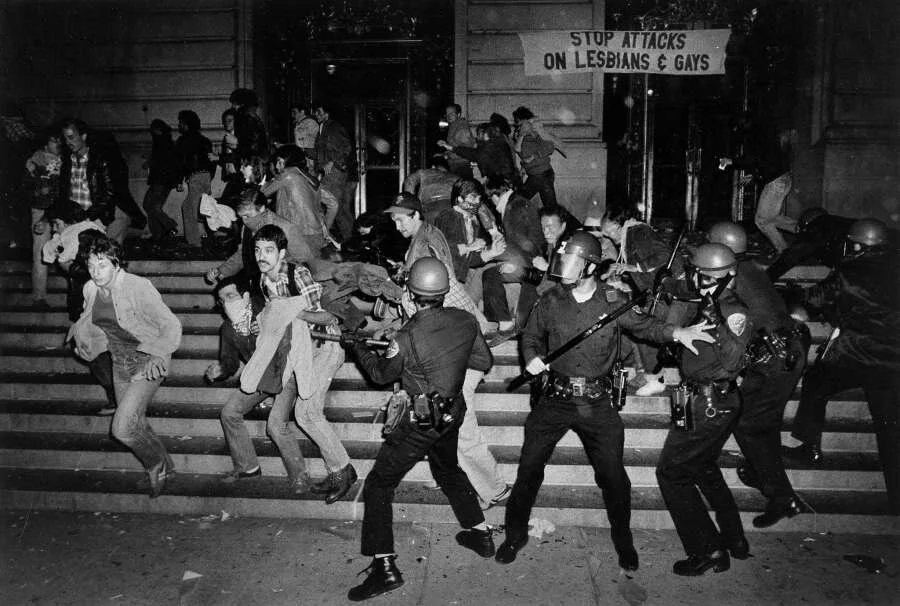

JB: “The right to not be bugged,” I love that. And it’s interesting, because when we talk about queer liberation, and the birth of the more widespread gay liberation movement, often we talk about different uprisings that have happened in different bars. Obviously there’s Stonewall, but even before that, there’s Compton’s Cafeteria, in the Tenderloin. So it is really interesting to me that the bars and restaurants and clubs that served gay people become this rallying site from which to create a larger political movement. It starts as being just about — “just” about — “no, we have the right to gather and drink with our friends,” and then it becomes this larger fight for dignity.

SE: Yeah, the bars, that’s the first level of it. That’s a place where we could gather safety and power, because it wasn’t safe on the streets, being harassed, especially if you were non-binary or genderqueer in some way. And there was just so much blatant homophobia on the streets, and violence, and especially by the cops.

Which is what Stoumen was trying to fight. They basically forced him too close. Even though he went through years of legal battles. And won. But it wasn’t in time to save it. So then, moving forward, these bar owners band together, and José I think was pretty instrumental in developing the Tavern Guild. That was the first gay business association in the country, founded in 1962.

Yeah. Wow. It’s really telling — it’s not surprising, but it’s telling — that the first gay business association in the country is the Tavern Guild. That early solidarity is organized around equal access to bars. And it was based out of San Francisco.

Jose Sarría, nicknamed the Nightingale of Montgomery Street for his operatic performances at the Black Cat, was instrumental in developing the Tavern Guild, initially drawing together gay bar owners (and heterosexual owners of gay bars, like Sol Stoumen) to raise funds to pay for bail money and legal fees, like the ones Stoumen was facing for his long court battles. While it was too late to save the Black Cat, which closed in 1963 after its liquor license was revoked by the ABC and it could not survive by selling only food and soft drinks, the Tavern Guild did go on to become a crucial organizing arm of gay liberation in San Francisco. SIR and the Tavern Guild were closely intertwined allies: SIR would meet at alternating bars whose owners were members of the Tavern Guild, drawing business on typically slow nights, and Tavern Guild members would donate food and drink to SIR for its parties.

Image courtesy of https://www.foundsf.org/index.php?title=The_Black_Cat_Cafe

Image courtesy of https://revolution.berkeley.edu/tavern-guilds-beaux-arts-ball/ via the Berkeley Tribe

The most major event that the Tavern Guild would sponsor was an enormous Halloween drag ball, the first of its scale in the Bay Area, first held in 1963 at the Jumpin’ Frog on Polk St. At the third annual of these Beaux Arts Balls in 1965, Jose Sarría was named Queen. Declaring that he was already, had always been, a Queen, he then named himself Empress, and the Imperial Court system was born.

One really interesting thing is that at a certain point, after all this police brutality that was happening with the bars — I’m really fascinated by this straight police officer who the commisioner assigned to the gay community, and this was a real turning point.

Wow.

Yeah. So the history is pretty massive: there was a New Year’s party that was planned at the California Hall, on Polk St., and it was organized by a bunch of priests, including Reverend Cecil Williams, from Glide Memorial Church, who was a major activist in the scene, and Ted McIlvenna, a minister who later was a key figure in the San Francisco Institute for the Advanced Study of Human Sexuality. They planned this event so that this alliance between religious leaders and the gay community would prevent police from breaking it down, and assert that these people actually had the right to gather, and be there together. And then there was a huge raid, the cops did not do as they had promised, even one of the priests got arrested — anyway, that’s a whole other can of worms, but it’s an important moment because through that event, the failure of that event, came this desire and need for there to be a dialogue between the police department and the queer community. And it was, really interestingly, the priests that were leading this — who were also, you know, getting money from the government to help combat poverty at the time, so they were able to invest more into this.

I’m really fascinated by Elliot Blackstone, the police officer tasked as an intermediary between the gay community and the SF Police Deaprtment. He worked closely with the trans community, too, after a number of folks approached him about the brutality and violence they faced. He was an ally. He was like, “you can’t just go in and start arresting people randomly.” But of course, this is all tied to years and years of this police brutality. In all the neighborhoods that we were in — Polk Street, North Beach, the Haight, the Castro — the raids were just everywhere.

Image courtesy of https://projects.sfchronicle.com/2018/sf-pride-timeline/ via John Storey/The SF Chronicle

So all that stuff is really important to name. So then, once we move forward, going into the seven gay bars in the Haight, we can start to talk about the differences between them and the kind of individuality that was starting to happen. Maybe that was always the case, I don’t know, but like in North Beach, with the very early gay bars, there were always differences — lesbians went to one place, there was one place that was more touristy — but I think there was more nuance happening in terms of individuality in the gay community, and different kinds of queers. For example, we would note the gay hippie bars, the more activist lefty crowd, sometimes those mixed, and then the “clone” crowd.

The Seven Gay Bars of Haight Street:

Gus’s Pub. 1446 Haight St. Gus’s was frequented by motorcycle guys and leathermen. It served only beer and wine, no hard liquor, and its backyard was notorious for potsmoking, political discussions, and gay sex. Eye Zen friend/collaborator and filmmaker behind The Cockettes, David Weissman, told us in an interview that at first it didn’t occur to him that Gus’s was a gay bar because “I had never seen gay people that looked like that before” — that is, not effiminate or flamboyant, but masculine and tough. Lefties and hippies frequented as well. The wallpaper was a collaged collection of obscene comics and photos.

The Question Mark. 1437 Haight St. Now Trax, having changed its name in the early 80s. Directly across the street from Gus’s, The Question Mark brought a slightly higher-class, less politically-radical & leftist crowd. It was decorated with moose heads, and ironically, had a giant framed photo of Gus’s Pub displayed on the wall.

The I-Beam. 1748 Haight St. The I-Beam was the first big gay club in the Haight — filling a crucial niche, because prior to its opening, gay gathering places in the neighborhood were smaller and thus more secretive/private. But the I-Beam was big, and loud, featuring rock and punk bands like Siouxsie and the Banshees, Duran Duran and the Cult, as well as their packed Sunday afternoon Tea Dances, which provided an environment in which gay attendees were the majority. There was a $5 cover charge to get in, to which the hippies were initially opposed, as they felt it was an infiltration of “clone” gays from other parts of the city who were hopping on the bandwagon without being invested in the political and social ideals which gay hippies stood for. Nonetheless, the I-Beam was wildly popular, drawing up to 1000 people a night, and was a huge part of the “gay renaissance” of the Haight in the late 70s and 80s (the I-Beam opened in 1977). Its often drug-fueled dance parties, however, were the target of numerous sound complaints from neighboring businesses hoping to shut down this bastion of gay nightlife. The I-Beam closed in 1992, unable to remain competitive with the South of Market clubs which were permitted to go all night, as well as the devastation of the AIDS epidemic.

Bones. 1840 Haight St. Now, Milk Bar.

Cadillac. 1511 Haight St. A historical gay bar, then reopened as The Deluxe in 1978. Along with I-Beam, the Deluxe was one of the popular spots responsible for the “gay renaissance” of the neighborhood — it was a trendy spot to play pool and cruise.

Mauds. 937 Cole St. Owned by Rikki Streicher, Mauds was a familial gathering spot for San Francisco lesbians for over 20 years, until its close in 1989. Men were welcome — as bartenders, as California law prohibited women from pouring drinks. Streicher hosted holiday dinners for folks who didn't have family or homes to return to. For more, see the film Last Call at Mauds.

Bradley's Corner. 900 Cole St. Bradley’s Corner was a neighborhood piano bar for nearly 40 years, the last 20 of which were distinctly gay. Gays and lesbians gathered together there, along with military personnel from the Presidio — some of whom, no doubt, were included in the first categorization — and folks sang along to the piano and played pool. Around the corner from Mauds, Bradley’s also had a familial vibe: every Tuesday, spaghetti dinners were offered for 69 cents, while Wednesdays were "hat nights": "Wear a hat and pay 50 cents for bar drinks" reads an ad from the time.

Of these, only Trax (formerly The Question Mark) remains as a gay bar today.

So anyway, I think a key theme here is identity, post-Stonewall. Or, let’s just say, during the height of Gay Liberation. Because Stonewall is only one event. I love that — in the book we’ve been passing around [Smash the Church, Smash the State: The Early Years of Gay Liberation, a compilation edited by Tommi Avicolli Mecca] it names three events, pre-Stonewall — if you think about it, there’s Cooper’s Donuts in LA (1959), there was Dewey’s in Philadelphia (1965), Compton’s Cafeteria here in San Francisco, in the Tenderloin (1966), and then of course there’s the Stonewall (1969). And all of them had uprisings. And out of that comes gay liberation. That’s one of the factors. Not tolerating the harassment anymore, and asserting our rights. And so — Gay Liberation Front, the Bay Area Gay Liberation Front, the Society for Individual Rights, the Tavern Guild — all of these organizations are basically playing off each other, and they are the next generation after the Mattachine Society and Daughters of Bilitis. I think that’s important to mention: there’s starting to become this new awareness of what our identity was, that our identity was nuanced, and that there could be different places for different people to be.

Right, and not just — my understanding of Mattachine and Daughters of Bilitis is that they were pretty straight-laced, like, “gay people, they’re just like you,” march in Washington holding signs and wearing suits and dresses. Assimilationist, because there wasn’t really another option. But later, to really be able to assert — you know, Compton’s was primarily Black trans women and drag queens who initially fought back. There was someone, we don’t know who she was, but she throws her coffee in a cop’s face, and that apparently is what starts the uprising. Beginning to assert ourselves as queer people as having lots and lots of nuance and different types of desires and wants for community and liberation. Feels like a really crucial turning point.

Yeah, it is a crucial turning point. So, in the early 60s, our rights are changing, and these different bars are opening, in the Haight. There’s more nuance and more individuality, distinguishing one bar from the next, different versions of “gay” you could be. And out of that a kind of a revolution is happening.

This idea of gathering in community is obviously huge. Cannot be overstated.

Yeah, the gathering. And in terms of gathering, we also have the Golden Cask, which David Weissman [interviewed for the oral histories we gathered] mentioned was a big gay hangout and a very good restaurant, at 1725 Haight, so it was up a little higher, closer to the park. And then there was Blue Front Deli, which is still around, and it was a gay-owned business, and then Mommy Fortuna’s Cafe, which is where the Cockettes hung out. So I think between those places, there was a lot of gay gathering spaces, to be out and be ourselves.

I think this is a great backbone to the story about how gay bars played a role in gay political awareness and liberation. I’m also interested in how these gathering places, combined with the spirit of sexual revolution in the 60s, impacted folks more personally, on an individual level, in their sex and romantic lives.

So should we talk about sex?

Let’s talk about sex. My next question is: what changed for queer people with the sexual revolution of the 60s? What didn’t?

In terms of sexuality, I think when you’re repressed for long enough, living under some other morality system that you don’t subscribe to, that, I would think, would make us want to express ourselves in the most free & open way. To be in private spaces where we could love ourselves; where we could feel both safe and comfortable to be able to express ourselves sexually. “Gay is good” was a slogan José [Sarria] coined — this belief that we could be together in the ways that we wanted to, it wasn’t shameful, and it could be less hidden. As opposed to the ten years before, at these gay and lesbian bars in North Beach, when as soon as a cop walked in, you go and you dance with a person of the opposite sex. There’d be a word, or a code, flickering the light off and on, and there’d be this switching that would happen.

It’s a pretty interesting example of solidarity between the two communities. “Okay, neither of us want to be caught in this situation, so let’s pretend — let’s be beards, while the cops are here.”

Yeah. So I think with those newer freedoms, then you add LSD into it, once the 60s come around, and people are like, slithering around, and just wanting to make love to everything in nature. There’s pot, and mushrooms, and other drugs, to kind of help us get more into our bodies and appreciate what we have, who we are, physically, as social, sexual, spiritual beings.

I love that a lot. I love this idea that in some ways the drugs that became super widespread in the 60s may have helped the culture in general but in particular queer people to feel a part of their bodies. And that was not something to be ashamed of, or to push away, but to really embrace.

Yeah. I mean, of course there’s also the opposite of that happening — rampant alcoholism and addiction, with people holding so much shame and internalized homophobia that it’s turning inwards on ourselves. As seen in movies like Boys in the Band, which was originally a 1960s play. So I think both of these things are happening simultaneously: drugs freeing us, and drugs taking a hold of us. And the different gay groups are going in different directions. Mattachine splinters off, as you were saying earlier, and the assimilationists are going further in that direction, into fitting in, versus Harry Hay and many others who were creating [Radical] Faerie circles, gathering together and seeing us as more whole, healthy, “normal” and unique in our own way.

That’s really interesting, this idea of uniqueness, because I wonder if that’s something that’s shifting for the culture as a whole, and not just within the gay liberation crowd. I wonder if it’s something to do with the 60s, and 70s, the hippie movement, anti-Vietnam war, this desire to not be seen as part of the machine of the nation, and everything it stands for, all of the norms that it upholds. I can just imagine, all of these kids who were born shortly after World War II, and raised in that shadow, beginning to split off, and say, “no, I want to be an individual, it is not the goal to blend in, have a white picket fence and a suburban home that looks identical to my neighbors’.”

Yeah. Even as [Eye Zen contributor, Out of Site interviewee, historian] Michael Sumner pointed out, really acutely, that going back even further, into the first and second World Wars, that San Francisco was a stopping off point, for people at sea, and for military personnel coming through town. A lot of people saw this as a place where they could be singular people. Straight people as well, but there was more opportunity for homosocial spaces. So SROs [Single Resident Occupancies] have long been vital to San Francisco, and they created more of these homosocial spaces, where men could be living all together, in single rooms, because they were itinerant workers, so they’d be going out to sea, wherever they were called to duty. And then, when people were coming back from the war, they were like, “am I gonna go back to this conservative village in Indiana, or am I gonna stay in San Francisco?” So that’s how a lot of people chose to remain here, as they came through here, and they saw the potential for freedom, even though there was still a lot of danger. It goes all the way back to those times, and the connection to military then. And Jose [Sarría] is really part of this generation, he served in the military, he was discharged… Gavin Arthur is another one. He also served in the military. So anyway, that’s a whole other story. But I love how those generations kind of intersect.

[Eye Zen contributor, interviewee, historian and friend] Joey [Cain]’s been talking to me too, about the first Faerie gatherings, the first Sissy Circles — they were really an outgrowth of Gay Liberation Front circles. They were events where political strategizing would happen more casually inside people’s homes, where they would get together and talk about politics. And places like Gus’s were hotbeds for that crowd. And then they were meeting, at Arthur Evans’ place, and there were a bunch of these houses, where people were getting together and going “no, we’re not gonna tolerate this, we’re gonna fight back.”

This connects to Atascadero, which was a mental hospital where gay people would be sent. They were giving lobotomies to gay people, they were doing electric shock treatments, they were doing aversion therapy treatment, where they would hook up nodes to their penis and shock them when they were thinking about gay men, or gay sex, or whatever. These people were tortured, and many never recovered, physically or mentally. Activist Don Jackson wrote an article titled “Dachau for Queers” that ran in the Gay Sunshine Press about his experiences visiting “patients” — inmates — there.

Wow. Oof. That is… strong imagery.

So that’s what we’re pushing up against. We’re seeing that, and we’re going “no.” Cause a lot of people don’t know this, but people have to know that. It’s really important.

Yeah. I mean, I didn’t know that. Or when I think about that [torture], I think about it in rural areas, conversion camps… I don’t think about it in the Bay Area.

Image courtesy of https://voices.revealdigital.org/?a=d&d=BGJFHJH19730316.1.7&e=-------en-20--1--txt-txIN---------------1 via Los Angeles Free Press, “California runs a ‘Dachau for Queers,’” March 16-26, 1973

Ok, speaking of the Bay Area. What role did nature or public parks play in queer hippie life? Part of what I meant with this question is not just the free sex, cruising spots but also, how did proximity to nature impact the culture and the ways that people related to each other? Because that is something that is unique to San Francisco in terms of other major cities in America.

Well that’s interesting that you bring that up, because Sunday I was feeling obsessed, trying to find more stuff, and I was rereading the interview with Michael [Sumner], and that’s one of the major themes that he got into: that especially the Haight, nature was a really important thing. LSD played a part in that, acid being a drug that puts you in touch with your body and the environment, that you’re in this state of presence. And Michael also mentioned that there was a whole group of radical queers from the GLF who were regularly going to different spots in San Francisco. There are more areas of nature in San Francisco than there are in most urban environments — and also they were going up to Russian River. That was the big hangout spot. And as we moved into the ‘70s and ‘80s, that remained, and still remains, a really important haven for queers. During the AIDS pandemic, a lot of people were going there to die, and thought they were going to die there. It’s so hard to say “they,” because everyone’s story is unique, but I’ve heard many stories of people going there to die, and then the cocktails happened, and they survived, and they are still there. I know a handful of people, who I’ve visited there, people I’ve known over the years. And you know, there are events, and bars there, the whole scene. But yes, I think nature’s really important.

And then there was, of course, sex happening in Golden Gate Park, at the Windmills, down near the beach, which has historically been a well-known gay cruising spot. And then there are all these bathrooms, within the park. There’s one particularly, right near the buffalo, that I’ve heard was a big cruising spot. Cause like, where do you go? You have roommates, they don’t know you’re gay, where do you go to have sex? But Buena Vista Park was really developed. I mean, you can still walk through there, and see the pathways that were created in different places. More on the Eastern side, off the beaten path, you can still see these pathways where you can walk between bushes. It’s all been opened up now, they’ve cut back all the bushes so it would stop — because it was like, a gathering space, there’d be dozens and dozens and dozens of people there, you’d go there to cruise people, you’d bring people there, there was sex happening all over the place. And then there was, you know, Bobby’s Victorian.

Well, we have to talk about Bobby’s Victorian, because as you know, this is one of my favorite details of the entire project.

I mean, he’s a fascinating character, Bobby Kent — he played in Glide’s band, he performed with Sylvester, he was really there in the moment. More connected, it seems, than most, in an interesting and unusual way. Why are you fascinated by him?

For some of the similar reasons you mentioned. Multiple different people have mentioned him, to you, to us, being like, “Oh yeah, he was there. That was him also,” and I’m always fascinated by the types of characters who tend to find themselves amongst different communities. There’s also something about the physical history — the built environment of the neighborhood. The fact that he had this job restoring old Victorians — you know, I grew up in a Victorian house up in the Fillmore, and have a lot of nostalgia for those types of homes, a lot of appreciation for how specific and weird a lot of their quirks are. So the fact that one of his crafts — he was a musician, among other things as well — but one of his crafts was this very loving restoration of these homes, not because it was profitable, back then, but because otherwise they were going to be torn down, and because he thought that they were beautiful, and they shouldn’t be torn down. And then to go and be like, “okay, I’m going to take scraps from these job sites I’m working on and go build a Victorian treehouse in the biggest cruising area in the city, and make it, like, an orgy treehouse — ” I also love that. I wanna know — I mean, the cops burned it down one night? I want to know, were there people there, did they see? Was there a raid on the park in general and then the cops burned it down in protest, or was it kind of in secret, like, toss a lit cigarette in, and then boom? I mean, I don’t know. That’s just — one of the details I’ve latched onto in this project.

Yeah. I love talking about this shit with you, Jax. It’s been really fun.

I feel the same way!

*both laughing*

Author-Jax Blaska: I’m a San Francisco-bred, East Coast-baked theatremaker and teacher now based in Oakland, and I’m the research & production assistant on Out of Site: Haight-Ashbury. These posts, we hope, will serve as companion pieces to our show as well as rooting our work in its rich historical context. I hope you enjoy. Yours in creative solidarity and ongoing queer liberation, Jax.

DEEP DIVE is a series of blog posts, dialogues, wonderings, and archival research into the history & culture of the Haight-Ashbury neighborhood of San Francisco in the 1960s and 1970s, and the queer & counterculture communities that flourished there. This series is the product of nearly 6 months of research and conversations, including oral history interviews & correspondences with Joey Cain, Michael Sumner, David Weissman, Jim Siegel, Fayette Hauser, Peggy Casserta, and Mike Caffee; books such as Smash the Church, Smash the State! The Early Years of Gay Liberation (Tommi Avicolli Mecca); Flower Power Man (Mary Lou Harris, Jayne Anne Harris, Eloise Harris); I Ran Into Some Trouble (Peggy Casserta); films such as The Cockettes (David Weissman, 2002) and Pickup’s Tricks (Gregory Pickup, 1973); and many more organizations, friends, and resources too numerous to name.

Follow us on social media to get updates on new posts and info on our upcoming production of OUT of Site: Haight-Ashbury!

This work could not happen without the support of our greater Bay Area community. Click below to make a tax-deductible donation that helps us pay our artists a living wage and provide low cost tickets to those with financial barriers. Be sure to select “Eye Zen Arts” on the fiscally sponsored project drop down menu.